ONE DEEP-DOWN AND DIRTY REASON WE SHOULD READ CHILDREN MORE FAIRY TALES

We are probably all familiar with Albert Einstein’s remark about intelligence …

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales.

If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.”

Arthur Rackham Hansel and Gretel

I have often wondered whether a quote like this, taken out of context and without Einstein’s imprimatur, might come across to non-believers as saccharine and indulgent, and as self evident only to those who already take such an idea to be self evident. Fortunately, this quote has Einstein’s name attached and thereby gains gravitas … but have we thought through why Einstein might have said it? And how many of us have followed his advice?

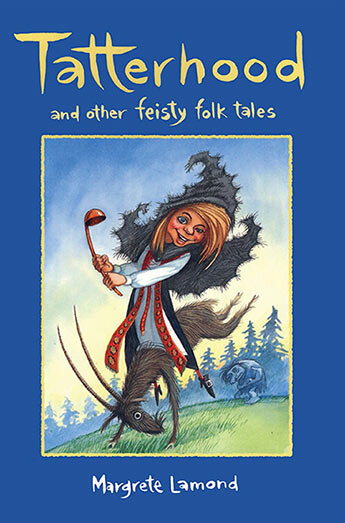

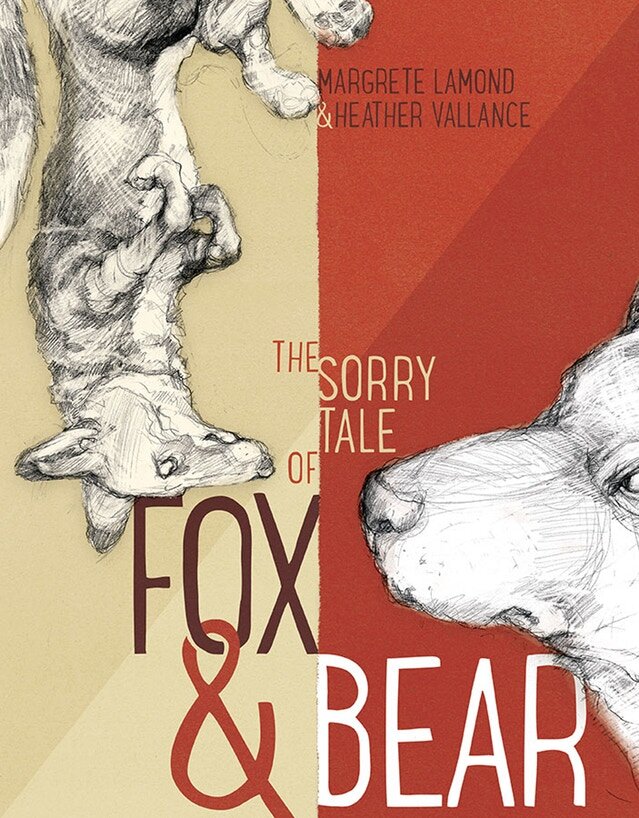

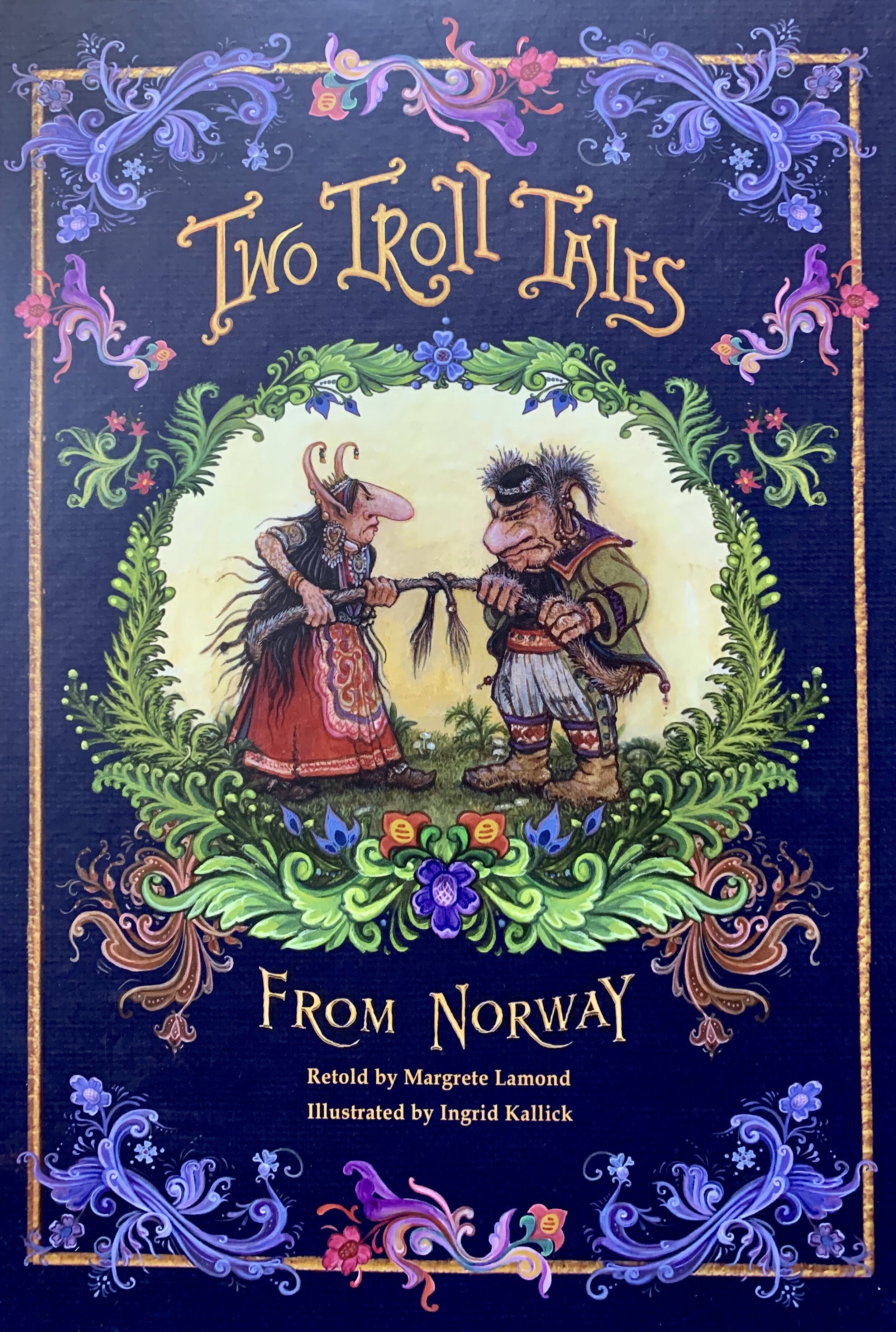

I know I have tried … I have an entire bookshelf devoted to the folk and fairy tales of the world, and have authored liberal literary retellings of several of the more obscure.

But while I have read many, I have not read most of the tales on my shelf, either to myself or to anyone else … and why not? Because the obscure tales than exist beyond the comfortable canon of the Top Twelve are, quite frankly,

WEIRD!

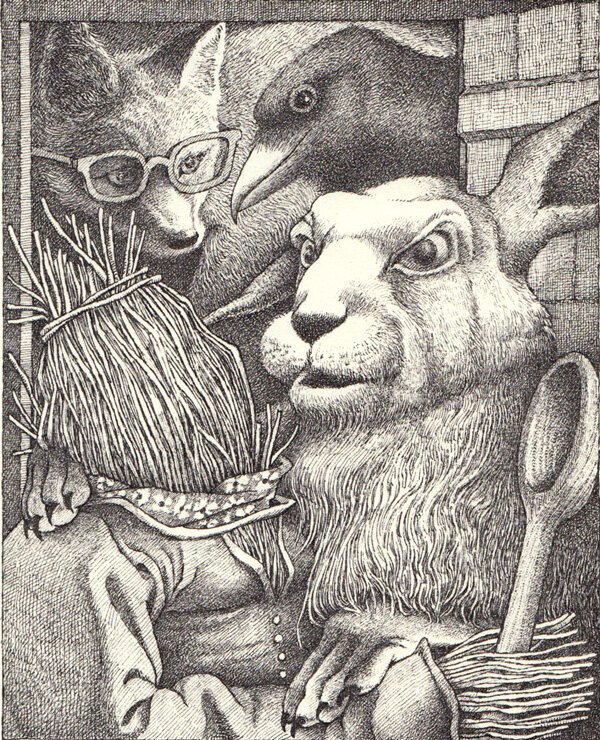

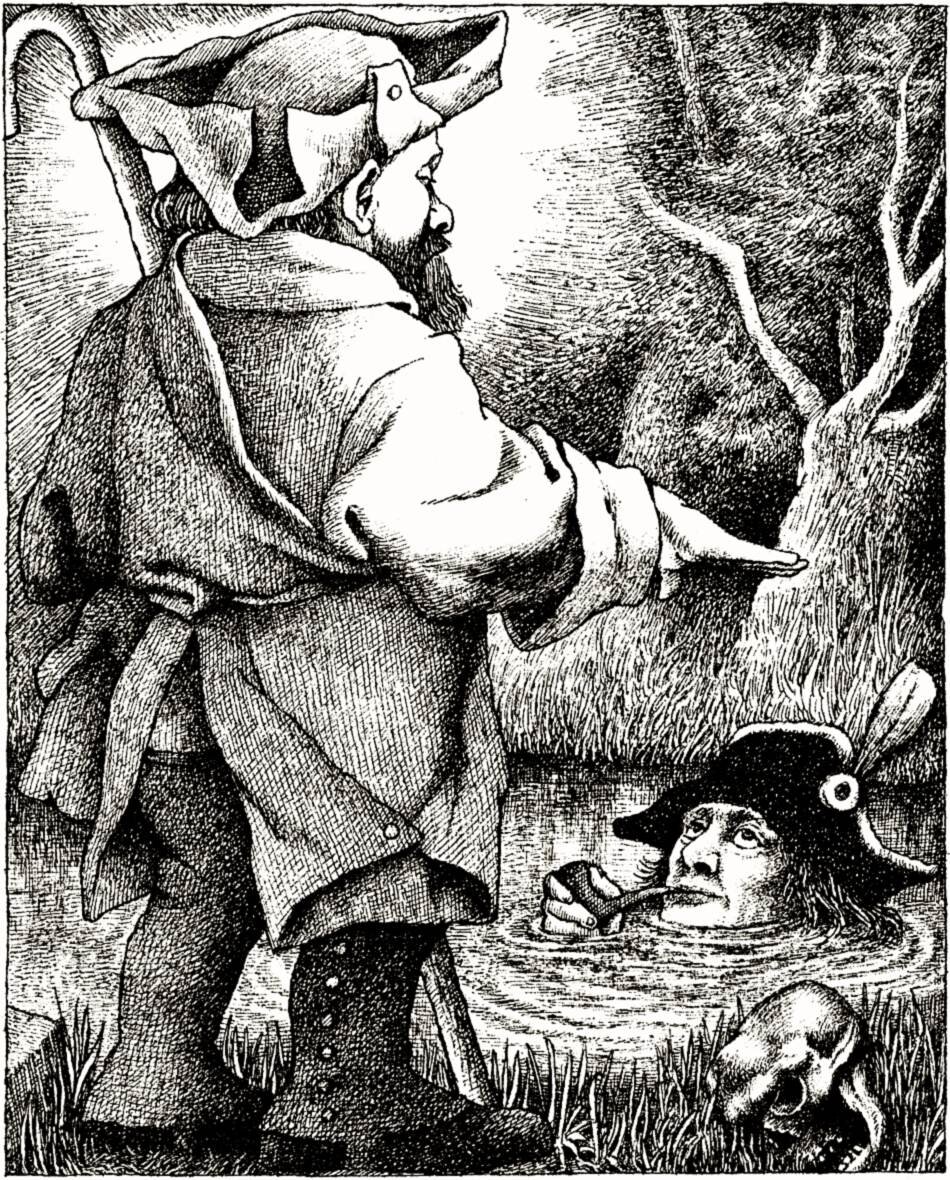

… as Maurice Sendak knew when he illustrated The Juniper Tree, about which Maria Popova said elegant things, and as evidenced by the sample illustrations below.

However, it is the WEIRDNESS of many folk and fairy tales that I take to be the crux of Einstein’s claim. The thing about fairy tales is not only that they are as many as the rootlets of an ancient tree but that they have - like those rootlets in their rocky terrain - probed, delved and insinuated themselves into the remotest cracks and crevices of the human psyche, finding vagaries and conflicts out of which to spin stories that explore and exemplify the broadest spectrum of what it is to be human.

So, of course, it isn’t the tales that are weird. It is we who are weird. It was we, after all - or others like us - who created these tales in our own image, and we who delved into our own psyches to tell stories about what we found hidden there.

Derek Collard’s illustration for Alan Garner’s retelling of Kate Crackernuts.

And what we found hidden was not just the simple seven deadly sins plus a smattering of virtues, but multiple nuances of those sins - such as rapaciousness, ambition, cunning, cupidity, spite, inanity - along with multiple nuances of the great virtues - including resoluteness, ingenuity, integrity, sacrifice, loyalty, humour and self-worth - all expressed in endless variations of sibling rivalry, abandonment, kidnap, theft, trickery and fratricide, to suggest a mere few.

So why read fairy tales, and more fairy tales?

Some proponents of reading suggest stories have social value because they model social mores, often by depicting violation of social mores and their ultimate restoration by the ‘good guys’. Others suggest that shared stories create shared identity, from which social cohesion grows.

But if we dig deeper into recent evolutionary research into the literary human, we find that stories do not so much instruct as simulate. Stories provide our brains - and therefore our emotions, bodies and minds - with opportunities to play with, taste and savour their events.

And what is savouring if not a form of feeling, and what is feeling if not a form of experience, and what is experience if not a form of memory, and what is memory if not knowledge?

I don’t mean knowledge in terms of ledgers of facts. I mean knowledge in terms of knowing how a particular nuance of emotion feels. Knowing, for example, how it feels to be rejected by your mother for your ugliness, reviled by the great and the good for the same reason, and to yet maintain the kind of perseverance, good humour and self-worth that helps you intelligently outwit, outdo and out-rank them all (the themes of Tatterhood and its many variations, as it happens).

Illustration for Catskin, by Arthur Rackham.

This is a complex mix of positive and negative feelings, a peculiar mix not easily entertained through real-life interaction in the hurly-burly of life, but readily available in bite-sized pieces in every weird fairy tale, each of which can be read in safety and comfort (all things being fair, of course, which they are sometimes not). The greater the range of these emotional cocktails we vicariously experience, and the more complex their combinations and subtler their gradations, the more neural pathways we develop, the more varied and complex these neural pathways become, and the more subtle our thinking is capable of being.

It is with this greater storehouse of complex neural pathways that one can entertain grades of possibility, as opposed to the easier option of stark extremes, and of simple black-and-white thinking. An intelligence that has played with the unfamiliar in stories is not as inexperienced when confronted with it in real life. And an experienced intelligence is capable of clearer thought.

Our world needs future adults who dare to think subtly and clearly, and to think beyond the prescribed and proscribed. Read your children more fairy tales.